During the summer, Ukraine’s victories winning Olympic gold medals in Paris made me think about the country’s resilience in the face of overwhelming odds. And just as you can see this strong drive among the athletes in sports, you can also see the spirit of resistance in the games that Ukraine is making.

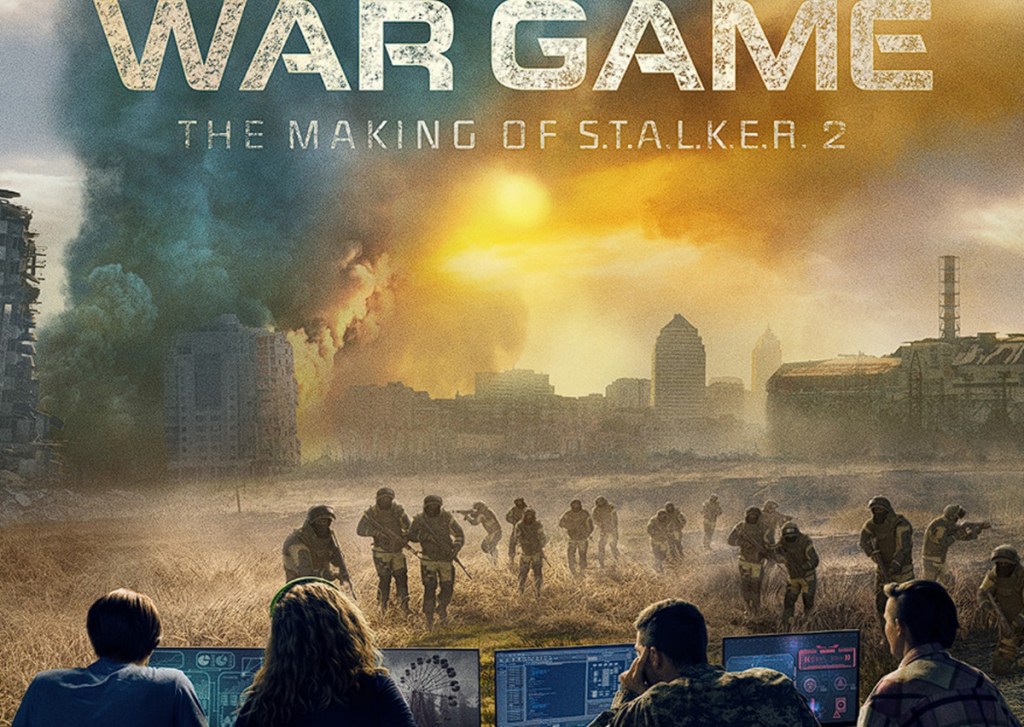

I just watched War Game: The Making of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2, the Xbox documentary about the best-known Ukraine game company, GSC Game World, as it struggled to finish Stalker 2: The Heart of Chornobyl, a triple-A game that has been in development in various forms for a decade. The team’s resilience in the face of war and other obstacles showed through in the emotional film, which is a kind of microcosm for the toil thousands of people working in games in Ukraine or in the Ukrainian diaspora — under the shadow of war where all of the odds are against them.

The developers battle the emotional toll of displacement, personal loss, and political upheaval. And they must find the strength and resilience to keep their artistic vision alive, the filmmakers said. With personal stories of sacrifice, determination, and hope, the film offers a powerful insight into the human toll of conflict and the transformative power of creative expression. The film was made by Andrew Stephan, who made a documentary with Tina Summerford about the 20th anniversary of the Xbox.

The final hours of the making of Stalker 2: The Heart of Chornobyl, and its recent appearance at the Xbox Showcase in Los Angeles in June, speaks volumes about the ability of Ukraine’s game industry to adapt and continue moving up the food chain in the game industry. For a relatively young country, Ukraine game devs have made remarkable progress in moving from external development (work for hire) to creating original triple-A games on their own during the relatively short period of freedom the country has enjoyed in the post-communist era. The film captured GSC Game World’s making of Stalker 2.

Join us for GamesBeat Next!

GamesBeat Next is almost here! GB Next is the premier event for product leaders and leadership in the gaming industry. Coming up October 28th and 29th, join fellow leaders and amazing speakers like Matthew Bromberg (CEO Unity), Amy Hennig (Co-President of New Media Skydance Games), Laura Naviaux Sturr (GM Operations Amazon Games), Amir Satvat (Business Development Director Tencent), and so many others. See the full speaker list and register here.

GSC Game World has been working on Stalker 2 for years, running into trouble through delays, cost issues, the pandemic and restarts. Then, in February 2022, the game was derailed again after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I saw the game in a behind-closed-doors demo for the press during Gamescom 2023, the big trade show in Germany. And this year, the game got its day in the limelight during Microsoft’s biggest showcase for games in a long time during the Summer Game Fest in Los Angeles.

In their outreach to fans, GSC Game World noted that you can donate to the Ukraine side of the war through Volodomir Zelenskyy’s web site. Since the game got a lot of visibility at the Microsoft Xbox Showcase, that kind of charitable effort can keep the plight of Ukraine more visible.

When we think about the challenges facing the game industry, we think about how people within it are able to adapt to change and remain resilient.

A long time coming

That was the theme of our GamesBeat Summit 2024 event back in May. Yet few have had to weather the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune like Ukraine’s game developers. It turns out many of them went through changes, endured the disruptions and still survive today. This story captures some of GSC Game World’s story in the documentary, but it also records voices from others inside and outside Ukraine.

GSC Game World shared the Xbox spotlight at Gamescom 2024, where I was able to interview the game’s leaders — Ievgen (CEO) and Mariia Grygorovich, (creative director) — a husband-and-wife team — about their arduous yet almost patriotically inspiring journey. They acknowledged they had one more delay — from September for a couple of more months later in the year — and now still expect the title to debut on Xbox and the PC on November 20.

With the launch of the documentary this week, we now know much more about their harrowing journey and what it was like to finish the game about a post-nuclear-disaster conflict — with supernatural elements and nightmarish monsters — while Ukraine was actually fighting for its life in a war with Russia.

When the war started in 2022, Ukraine was home to an estimated tens of thousands of game developers, working for companies such as Ubisoft, GSC Game World, Best Way, Wargaming, Action Forms, Xsolla, 4A Games, N-Game Studios, Мeridian’93, Frogwares, Boolat Game Development Company, Dereza Production Studio, Persha Studia, Cyber Light Game Studio, Playtika, Plarium, Pingle, Overwolf, DraftKings, Kevuru Games, Pinokyl Games, Vostok Games and Deep Shadows.

One count in 2018 showed about 200 companies. But later on, the estimate rose to around 500 game companies in Ukraine — many of them small indie studios. Many of the stories of starting up were similar.

Pingle Studio began when two friends, Dmytro Kovtun and Konstantin Shepilov, got together in Dnipro, Ukraine. I asked them if they were programmers back then. They joked, “We were players.” And they helped local developers complete their video games before the studio’s official founding in 2007 and grew to a company of more than 400 employees and three offices in three countries.

By mid-2023, when I talked to them, the company had contributed to more than 80 games. They were working on as many as 20 games at once. Somehow, they and other game companies in Ukraine managed to keep on working during the war where missiles rained down almost daily.

Elena Lebova, a Ukraine advocate who helped organize trips for Ukraine game devs to Gamescom even during the war, thinks there were around 30,000 Ukraine game devs. About 10 companies showed up at the Gamescom booth this year. They displayed bent artillery shell casings that had been turned into works of art. They auctioned them off during Gamescom, raising money for the cause.

The country had a lot of technical talent, born at great universities with strong computer science and art programs. That attracted foreign game companies to set up shop, and it helped spawn home-grown organic studios in the region over time. Some had operations in Israel, some in Russia too. This rich and storied ecosystem in gaming was entirely disrupted as the fighting broke out, with many developers going to fight. Ukraine was moving up the game industry food chain as many others had, following the model of regions like Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany and more.

Yet the interruption of this evolution is what has happened to Ukraine, and as Microsoft’s documentary has pointed out, GSC Game World’s story and the story of Stalker 2 is a microcosm for what is happening across all of Ukraine.

A shock to all Europe

The war was both predictable and yet still an unbelievable shock. How could such civilized societies with enormous populations descend into the barbarism of war in the 21st century? And after the war in Gaza started in October 2023, some companies like Plarium had people in both Ukraine and the Middle East — two different war zones.

In hindsight, the war seems predictable as the logical conclusion of Putin’s ambition to restore past Russian glory — and the clash with a spirit of independence that has driven Ukraine throughout its history.

Ukraine declared its independence from Russia on August 24, 1991, just five years after the horrific Chornobyl nuclear accident and two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In the post-Soviet brave new world, two brothers started making games after their father chose to buy them a computer instead of buying a new car for the family. In 1995, Sergei Grygorovych, the older brother, started GSC Game World to make ambitious interactive software that would put Ukraine on the map in gaming.

Stalker: Shadow of Chernobyl came out in 2008, and it was a success as a first-person shooter. It combined ideas from the novel Roadside Picnic with the real-world disaster of the Chornobyl nuclear meltdown, positing that this created a Zone where hunters known as Stalkers could go to find anomalous treasures. But they ran the risk of running into enemies including monsters unleashed by the radioactive contamination.

Two more Stalker games came out, but none of them were called Stalker 2.

Ukraine was casting off 300 years of Russian rule and seven decades of Soviet central planning. Yet Russia didn’t want to lose its empire — and the breadbasket of Ukraine. Only 13 years after the declaration of independence, the Russians under Vladimir Putin invaded, trying to take Ukraine back. At first, it was just a battle over a few provinces, including Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk.

As the saber-rattling started again in late 2021, and while work on Stalker 2 was well under way, Mariia Grygorovych feared the onset of war. The leadership team decided to make contingency plans that are detailed in the documentary.

As Putin launched a full-scale war on February 24, 2022, a refugee crisis ensued that drove as many as 8.2 million of the population of 41 million out of the country in the following year. I interviewed the leaders in August at Gamescom, and I also watched the film.

Life in the war zone

Back in April 2022, when I was interviewing Pavel Izotov, the maker of the Rebuild Ukraine mobile game, he paused multiple times to wipe tears from his eyes. That was very human and understandable, as he was making his game in the middle of a war zone. Izotov was living with his wife Irina in central Ukraine in a city called Cherkasy.

Around that time, barely two months into the war, Levvvel estimated gamers and game companies had donated more than $195 million to charities related to Ukraine, including $144 million donated by Epic Games and Fortnite players alone.

Ukraine had a history of good universities with graduates with technical skills, and so it became a haven for external game development. Work-for-hire is often the way that would-be game developers get experience and work their way up the food chain to be the primary creators of games.

During the iPhone mobile gaming boom, many of those developers became full-fledged game makers. I recall that the team at Gameprom made a pinball game on the iPhone in 2010. They didn’t grow up with pinball, but learned how it worked by watching YouTube. That showed a lot of ingenuity.

But much of the work came to a halt when the Russians attacked. In the initial panic of the war, many people moved away from the front lines, winding up in the west in Lviv, or outside the borders in Poland. When the country did not fall, Western aid arrived, and Ukraine’s front stabilized, the game companies managed to get back to work.

When the war broke out, Izotov was stunned and wanted to find some way to help. But he couldn’t join the military for health reasons. For the first week, the horrors of the war on the news were so disturbing that Izotov couldn’t do any work. He and his wife spent time talking to friends in different parts of the country and following the news of the invasion. They knew people in multiple places that had become the center of the fighting. And they had friends who had become soldiers for the Ukrainian army.

“It has been really emotional. And we are talking with our neighbors about how, if the Russians come to our city, how we’re going to defend this,” Izotov said. “And some of my friends did leave the city.”

Izotov and his wife decided to make a game focusing on raising money for the Ukraine cause. Working on a laptop in a bomb shelter, Izotov managed to post the Android game, which is all about rebuilding the country of Ukraine one building, landmark, and statue at a time.

“Every step that we take is about how can we best serve Ukraine,” he said in an interview with GamesBeat. “I want to help my country, to help my people, and do everything that I can do.”

By contrast to Izotov’s effort, Hendrik Lesser of Lesser Evil, a game developer/publisher from Germany, created something much different: Death From Above. In the game, you operate a drone and drop grenades on Russian soldiers and tanks below. This is a controversial game that brings politics in games together in an uncomfortable way, and in a panel at Reboot in 2023 with me, Lesser made no apologies for that.

Lesser said the company is “uncompromisingly anti-authoritarian, anti-racist, and pro-democracy.” And it will publish video games with clear political or social intent and messaging. Lesser believes that video games are this century’s most widespread, impactful, and important cultural medium. As works of human expression, they should be emotional and make the player feel something, he believes.

Ripped apart

For a time, all work in Ukraine collapsed. The power went out. The internet was gone. There weren’t any Starlink satellite internet connections available from Elon Musk yet.

Wargaming, the maker of World of Tanks, started out in Minsk, Belarus, but it moved its headquarters to Cyprus in 2011.

“We cold-bloodedly analyzed the ecosystem. It’s an EU country. It has democracy, the rule of law, a sound business system, lots of services. It’s not the biggest country in the world. But we studied a lot of other places,” said Victor Kislyi, CEO of Wargaming, in an interview with GamesBeat.

By 2022, Wargaming had 5,400 people, thanks to more than 140 million downloads of the popular free-to-play tank battle game. Then, as the war started in February 2022, Wargaming split apart.

“Before that we had prepared buses, passports, names of family members for immigration. As well as other aspects of safety. It is what it is,” Kislyi said. “In February I remember waking up, making a cup of coffee, and reading the news. ‘Oh my God.’ The first supernova in my head was, ‘We have 450 employees in Kyiv.’ Their safety was our immediate priority and focus.”

There was tension between those with Ukrainian or Russian roots.

“We got everyone together as best as practically possible, and there wasn’t much argument. We took the decision to completely abandon, leave untouched, the market of the Russian Federation and Belarus,” Kislyi said.

Work came to a standstill, and Wargaming began moving people, who were working on World of Warplanes, from vulnerable areas to the western side of Ukraine. Kislyi told me that his company had to decide to “be on the right side of history.”

Wargaming decided to part ways with its Russian and Belarus development studios, and its ranks shrank down as low as 2,800 people in a very short time. With its formal announcement on April 4, 2022, the company said it was leaving both Russia and Belarus and separating from employees who stayed.

It created studios in places like Poland and Serbia, and it added to its headcount in other places, growing back to about 3,500 people, including hundreds still in Ukraine. All told, it lost a third of its development capacity and a third of its revenue disappeared overnight as it cut off play in Russia and Belarus, resulting in $250 million in lost revenues. It was a very painful extraction, as detailed to me in an interview with Kislyi. But it was worth it, he said, and Wargaming still has hundreds of developers in Ukraine.

Life in the shadow of Chornobyl

It is hard to underestimate how significant Chornobyl was to Ukraine. In 1991, the new government took over the management of the 1,000-square-mile area of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. It was closed until the early 2000s.

After that, Stalker-like people went into zone, which had been overwhelmed with nature growing over human habitats. There were Stalkers in real life who went in with a map, a backpack and a radiometer. Pavlo saw a pack of 20 wild boar when he went into the zone. They got the feeling of what it was like to explore a place that was forbidden. The place was frozen in the time of 1986.

Current CEO Ievgen Grygorovich’s older brother, Sergiy, started the company and Ievgen learned how to make games by starting out as a playtester in the company. The original game was set in the Mayan fantasy world, but Sergiy wanted to tie the game to Ukraine’s own history, including the nuclear disaster at Chornobyl in April 1986.

Seeking to experience the real world that their game was trying to capture, the GSC Game World team went into the No Man’s Land of Chornobyl, where radiometers still detected radiation. As they shifted the game’s focus, they decided to make the game about the disaster in some way.

While many Russians and Ukrainians died heroically trying to prevent the radiation from spreading, the Russian incompetence in preventing the nuclear disaster through better design was not lost on the Ukrainians. One developer named Pavlo in the documentary noted his grandfather died of cancer. Ievgen noted in the film that those disaster workers sacrificed their lives to save others from the spreading radioactivity.

Mariia Grygorovych said in the film her mother was pregnant with her at the time of the accident and fled to escape the fallout so her baby would live.

Art capturing real life

In fact, the prior CEO, who was Ievgen’s brother, asked him to make Stalker 2, and Ievgen said no because he didn’t think the team was ready to take on such a big project.

But he eventually relented. “It was a crazy business decision to start this project, but we were sure that we would do everything possible,” Ievgen Grygorovych said in our interview.

Abandoning earlier directions, they created a plan and built a new team. They worked on getting the script right from the start. After six rewrites, they finally started moving forward.

Even without these external challenges, the game was ambitious, even for developers who had been working on games for decades. The team started with new technology. They came up with a list of tasks and broke it down into hundreds of thousands of tasks, Ievgen Grygorovych said.

The team would go into the Zone many times to record the details of what it was like so they could put them in the game. Sergiy left the studio in 2011. Eventually, his younger brother Ievgen took over. And Mariia, married to Ievgen, joined the company to be a crisis manager for just a few days. She eventually became creative director and is still working on the game eight years later.

And the pent-up demand for the new game is huge. With so many passionate fans of the first series of games, they are ravenous for more. The team announced the sequel, Stalker 2, in 2018. The company worked through 2020 and 2021 with the expectation of a 2022 release. It was not to happen because of the war. Russia escalated its threats in late 2021.

Mariia Grygorovych grew more and more nervous, and the team created contingency plans to move the developers from the capital of Kyiv to Uzhhorod on the Slovakia border. Buses were parked 24/7 outside the headquarters starting in January 2024.

Escape

Even so, it was easy to believe the worst would not happen. When war broke out, people had to decide their fates quickly. About 139 employees decided to stay behind in Kyiv, while 183 went to the border town in the buses.

Work continued on the game. Then people came in on a Sunday and packed up and moved. One dev said he took his Xbox out of fear he would never come back. The relocation took many hours, as Ukraine is the biggest country in Europe.

Another dev, Anastasiia, said in the film she had a dream that night that a huge metal structure was falling on her. She woke up to war. One of the places targeted for attack were power plants. Chornobyl itself became a battleground.

“It was the scariest moment of my life,” Mariia Grygorovich said about the start of the war.

The team concluded the safest place would be outside the country and moved to Hungary. The border traffic was horrendous, and the buses were stopped just shy of the crossing.

Mariia Grygorovich and about 45 or so members of the team and families walked across and had to plead with border guards to get to the other side. One dev said, “I felt like a traitor” for leaving the country. Eventually, Ukraine made it illegal for men to leave the country. One dev named Dymitro joined the armed forces on the first day of the war. He wore a Stalker backpack. Kyiv was close to encircled and it was believed it wouldn’t last a number of days.

One soldier/dev said he saw video of his apartment building on fire in Mariupol.

“I hated this helplessness,” the dev said. “You just no longer felt like you were in control of your life.”

Meanwhile, the game team had no equipment. They could not do photogrammetry, motion capture and audio recording. Yaroslav, a dev, wondered if they could ever get back to work on the game. The team found an office in Prague in the Czech Republic to set up shop again.

They had to start over on a lot of the audio capture. They rebuilt the capabilities from scratch. For those who went to fight, GSC Game World kept them on the payroll. The company also decided not to sell the game in Russia, even though Stalker had a lot of Russian fans. Every day, hackers tried to break into the company. The game became a means of resistance, that the company could not be stopped.

The team demoed the game for the first time at Gamescom in August, 2023. Fans waited five hours to see it. By this time, many of the members of the company had lost family members or loved ones in the war.

“We load our weapons with one hand and we make the game with the other,” one dev said in the film.

Finishing Stalker 2

GSC Game World managed to survive and continue working on Stalker 2 from the company’s base in Kyiv. When the war started and Ukraine lost a lot of territory to Russia, the attacks on infrastructure made life difficult. Electricity came and went, and internet access was also difficult to obtain.

Ievgen Grygorovych and Mariia Grygorovych kept watch over their 460 employees. Since the war started, they have spread out into new locations such as Poland and Prague and elsewhere, with some working remote.

During all this time, they never considered shutting down the game. They felt like a responsibility toward their country to get it done, to put Ukraine on the map of the game development world. When they saw their countrymen and women win medals at the Summer Olympics, they were proud, and they want the country to be proud of their work on Stalker 2. It’s been a hard road and the longest journey. What’s the ultimate lesson? In game development, you have to really love the process, Mariia Grygorovich told me.

We’ll see if there is some kind of happy ending, after the game launches on November 20.

Losses on the long road

As allies supplied munitions to Ukraine and the forces of Ukraine held back the Russian advance, the war front stabilized and the business side also stabilized. Elon Musk’s Starlink, based on satellites around the Earth, made it possible to get internet access throughout the country. Many game studios relocated to either remote work or set up offices in Lviv.

Many of the men either had to go fight in the army or continue working inside the country, as they were required under law to stay inside Ukraine. Others set up in satellite offices in other countries in Europe. At least a few Ukraine game developers have died.

Game animator Andrii Korzinkin of 4A Games, maker of Metro, died in combat. And Voldymyr Yezhov, a developer on the original Stalker game from GSC Game World, was also killed in the war. In December 2022, he died in a battle near Bakhmut, defending the city from Russian attackers. Oleksiy Khilskyi, a voice actor on Stalker 2, was slain. Maria Grygorovych of GSC Game World said there are tragedies every day or week as more and more people are killed.

I met with members of Ukraine game studios last year at Gamescom in Germany. They spoke of determination to carry on, continue fighting, and working as much as possible where business runs as usual. But they also wanted people to remember that they were fighting for freedom and democracy, and they needed the help of the world to survive the continuous onslaught of much bigger Russian forces.

Still, during the pandemic and the war, many of the Ukraine companies survived even as layoffs and shutdowns were spreading through the game industry across the world. The pandemic demand for games skyrocketed, game companies staffed up, but then the demand subsided as people went back outside.

Sometimes the war disruptions are small, but they remind everyone of the dangers. In Dnipro, Ukraine, a fragment hit the office building and destroyed a window. The office belonged to Nordcurrent, a mobile game company.

The game company is based in Vilnius, Lithuania, but many of its mobile game developers were based in Ukraine. Nordcurrent CEO Victoria Trofimova told me in an interview in the spring of 2023 that the team has worked under unbelievable conditions, like when a Russian missile landed less than 200 yards away from the Nordcurrent office in Dnipro, Ukraine. This kind of thing changes your workplace.

“Before the war you could say – you usually didn’t talk about politics at work. It’s a private topic,” Trofimova said. “The war changed that. It’s very much a topic. Whenever I have meetings online with our employees, the first thing we discuss is usually recent events – what happened, what they think, where things are going, how the Ukrainian forces are doing. That’s what we start with, and usually what we finish with.”

In the company’s mobile games, there are many more instances of details with Ukraine traditions and Ukraine pride.

The Ukraine diaspora

Last November, I also attended the DevGamm game conference in Portugal, which has liberal immigration rules and a sizable Ukraine expat population.

There, Lerika Mallayeva, who founded the FlashGAMM game event in 2008, told me that her company was thrown into chaos on the day of the Russian invasion, which was not a total surprise but still shocking when it finally happened.

Mallayeva had worked hard to build a company as the environment around her shifted. The company was sold in 2009, again in 2013 and she bought it back in 2017 and restarted under the DevGAMM name. The conferences were either in Ukraine or Russia. In 2019, the DevGAMM events drew more than 5,000 people. Before the pandemic, the biggest event was in Minsk.

But the pandemic hit and shut all the conferences down.

“We had to adapt,” Mallayeva said. “We did a lot of online events.”

For 2022, as COVID subsided, DevGAMM planned three major events. Then the war started early that year.

“We lost it all,” Mallayeva said.

Of the 10 people on staff, many moved. Half the team went to Riga, Latvia, and others scattered. One had to return to Ukraine for a family reason. They had to relearn how to do events in new cities.

“We have a family style business,” Mallayeva said. “We wanted to keep the team together and keep growing.”

The team is still spread across Eastern and Western Europe. They still managed to do one event online and one in person. By 2023, they were back with three events in other countries, such as Portugal, where I talked to Mallayeva. At those events, it wasn’t unusual to see the diaspora of both Ukraine and Russian expats. Another DevGAMM event will take place in November in Lisbon.

The day of the invasion weighs heavily on those affected by it. Michael Kuvshynov happened to leave Ukraine just five days before the war started to celebrate his birthday in the Czech Republic. Another dev in the film said he, his wife and infant son planned to leave the country on February 24, 2022. But that was the day the war started. They went to a bomb shelter instead.

After the war started, Kuvshynov moved around a lot and eventually landed in Los Angeles, where he was able to continue working with the ability to travel abroad. Men of military age are not allowed to leave Ukraine. These are things that other young men making games have not had to worry about.

The stakes are still high. When the war started, a lot of Ukrainian companies lost contracts. International partners were pulling out because of the risks. They could not continue to operate in Ukraine. This forced some companies out of business, but others also survived by creating their own games.

“We kept fighting,” Mallayeva said. “The message the Ukraine companies bring to us at international shows is they are still doing their jobs. Sometimes better than anyone else because we have more to lose.”

Back in November, 2023, Mallayeva expected to get 400 people at an event in Lisbon. More than 600 showed up, many from the Ukraine diaspora. The women-only team could still operate, as only men were not allowed to leave the country. The team chose to relocate one event to Lithuania. And then they switched it to Poland. Mallayeva doesn’t expect to do events in Russia anymore.

“Before the war, I didn’t care about politics at all,” she said. “I didn’t follow the news. It’s just hard for me to see how we are sometimes divided because of war and everything.” her company will hold another DevGAMM gaming event in Lisbon in November.

Are game fans aware?

Meanwhile, fans continue to play games around the world, often not realizing that these games are made by people in war zones. That’s what the Stalker 2 documentary reminds us about.

“Many fans, driven by their intense love for these franchises, sometimes lose touch with the fact that real human beings exist behind these fictional games they cherish,” said Andrew Stephan, the filmmaker, in his director’s notes about the film.

He added, “This film isn’t just about the hardest game development of all time. It’s about resilience and the unyielding human spirit in the face of unimaginable challenges. It’s about the importance of creation in a time of destruction … a defiant act of making something meaningful in the face of adversity.”

Source link